Unmasking Jack the Ripper: A Fresh Investigation into the Whitechapel Murders, Part 6

Posted on 06/16/2025 at The Curmudgeon’s Chronicle

The Solution – Charles Cross, the Ripper, and the Defense

We’ve walked the blood-soaked streets of Whitechapel, from Mary Ann Nichols’ murder in Buck’s Row to Mary Jane Kelly’s horrific end in Miller’s Court. Five women, the canonical victims of Jack the Ripper, fell to a killer who terrorized London’s East End in 1888, leaving behind a mystery that has haunted us for over a century. Through each murder, we’ve evaluated four suspects – Charles Cross, Joseph Barnett, Aaron Kosminski, and David Cohen – using only 1888 evidence to piece together the puzzle. We’ve examined timelines, witness descriptions, and the killer’s evolving savagery, narrowing the field with each step.

In this sixth part of our investigation, it’s time to name my top suspect: the man I believe was Jack the Ripper. I’ll lay out the case against him, detailing why he fits the crimes, and then present the defense’s counterarguments, putting him on trial before you, the jury. In the next part, I’ll have the final word with my rebuttal. Let’s step into the courtroom of history and unmask the Ripper.

The Case Against Charles Cross: The Ripper Revealed

After sifting through the evidence, one man stands out as the most likely Jack the Ripper: Charles Cross, also known as Charles Allen Lechmere. Cross, a 39-year-old carman working for Pickfords, was a seemingly ordinary East End resident with a wife and children, living at 22 Doveton Street, Bethnal Green, in 1888. But beneath this unassuming exterior lies a chilling connection to the Whitechapel murders – a connection that begins with his undeniable presence at the first crime scene and weaves through each killing like a dark thread.

Cross’s story starts with Mary Ann Nichols on August 31, 1888. At 3:40 a.m., he was standing over her body in Buck’s Row, mere minutes after her death – Dr. Rees Ralph Llewellyn estimated she was killed between 3:37 and 3:40 a.m. (inquest, September 3, 1888). Cross claimed he found her while walking to work, joined moments later by Robert Paul, but the timeline is razor-thin. PC John Neil arrived at 3:45 a.m., noting blood still oozing from her throat, yet Cross claimed he saw none, despite standing “where the woman was” (inquest). He told PC Jonas Mizen that “a policeman wanted” him, a false statement since Neil arrived independently, suggesting Cross may have misled Mizen to avoid scrutiny – especially since he spoke without Paul hearing (inquest). Cross’s calm demeanor – examining Nichols, waiting for Paul, reporting to Mizen, and going to work – stands in stark contrast to Paul’s fright (inquest). Further compounding suspicion, Cross used the name “Charles Cross” at the inquest, not his legal name, “Lechmere,” which he used in census records (e.g., 1891 census) – was he trying to distance himself from the police’s attention?

Cross’s proximity to the murder scenes is a consistent thread. He lived at 22 Doveton Street – 0.5 miles from Buck’s Row (Nichols), 0.8 miles from Hanbury Street (Chapman), 1.2 miles from Berner Street (Stride), 1.5 miles from Mitre Square (Eddowes), and 0.9 miles from Miller’s Court (Kelly). His mother’s 1888 residence at 147 Cable Street, where she lived with one of his daughters, places him even closer – 0.7 miles from Hanbury, 0.4 miles from Berner Street, 0.5 miles from Mitre Square, and 0.7 miles from Miller’s Court. Cross’s East End roots (born in Soho, 1849; lived in Sion Square, 1861) and family ties suggest he knew these streets intimately, a knowledge the Ripper needed to strike and vanish.

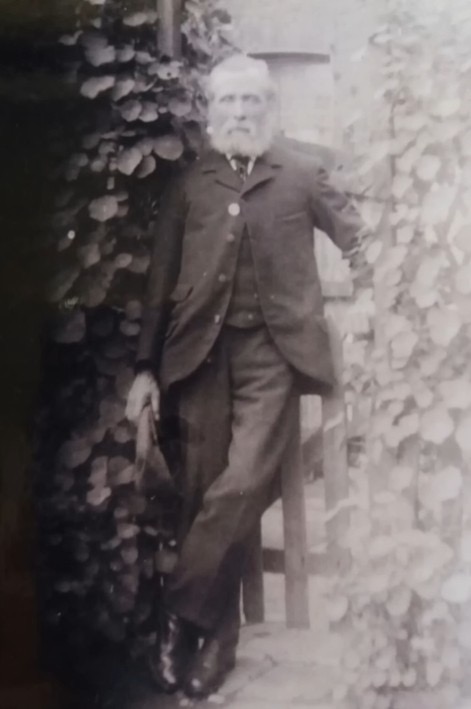

Charles Allen Lechmere, 1912

The timing of the murders aligns with Cross’s life as a carman. Nichols (3:40 a.m.) and Chapman (5:30 a.m.) fit his early commute to Pickfords’ depot in Broad Street, 1.5 miles from his home – a route that likely took him near Buck’s Row and Hanbury Street (historical maps, 1888). The double event (Stride at 1:00 a.m., Eddowes at 1:35 a.m.) occurred on a Saturday night into Sunday morning, Cross’s likely night off, giving him the freedom to roam Whitechapel. Kelly’s murder (3:00 a.m., November 9) was on a Friday morning, aligning with his early hours, though it’s earlier than his typical commute. Cross’s schedule gave him opportunity, and his familiarity with the area provided the means to escape.

The Ripper’s progression – from Nichols’ crude cuts to Chapman’s precision, Eddowes’ surgical skill, and Kelly’s savage overkill – could reflect Cross learning as he killed. As a carman, he had no flesh-cutting trade, but he may have handled animal carcasses at Pickfords, which dealt with goods like meat (historical context, 1880s logistics). His calm at Nichols’ scene suggests the nerve needed for such acts, and his presence at the first murder – 100% confirmed – sets him apart. No other suspect can be undeniably placed at a crime scene, and Cross’s behavior raises red flags: the false name, the Mizen discrepancy, the lack of blood on him despite proximity.

Witness descriptions are inconsistent, but Cross fits broadly – Elizabeth Long’s “shabby-genteel” man (Chapman, 40-ish) and Joseph Lawende’s “sailor-like” man (Eddowes, 5’7”, 30-ish) align with his age (39) and working-class appearance (inquest, web ID: 21). The lack of a clear motive – unlike Barnett’s jealousy or Kosminski’s madness – might point to a hidden rage, perhaps triggered by Nichols’ encounter on his commute, spiraling into a series of killings. Cross lived quietly until 1920, dying at 70 (death certificate, St. George’s Hospital), never suspected by police in 1888 (MEPO 3/140). But he was there all along – hiding in plain sight, staring at us through history.

The Defense: Why Cross Isn’t the Ripper

The defense steps forward to challenge the case against Charles Cross, arguing he’s an innocent man caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Here’s their counterargument, based on the same 1888 evidence.

Cross’s presence at Nichols’ scene proves nothing – he was a working man on his way to Pickfords, a route he took daily, when he stumbled upon her body (inquest). The tight timeline – minutes after her death – means he would have had no time to kill, mutilate, and clean himself before Paul arrived 40 yards behind him (inquest). PC Neil saw blood oozing, but in the dim gaslight of Buck’s Row, Cross missing it is plausible, as Paul also saw none (inquest). The lack of blood on Cross, despite the killer likely being splashed, supports his innocence – Inspector Abberline noted no blood on suspects like Barnett either (MEPO 3/140). Cross’s calm demeanor reflects a practical man, not a killer – Paul’s fright doesn’t mean Cross should have panicked (inquest).

The “false name” argument is overstated. Cross used his stepfather’s surname, “Cross,” which he’d lived under as a child (1861 census), and there’s no evidence he intended to deceive – he gave his correct address and occupation (inquest). The Mizen discrepancy – “a policeman wanted” him – could be a miscommunication in the chaos of the moment, as Mizen’s testimony is ambiguous (inquest). Cross’s proximity to the murder scenes is unremarkable – he lived and worked in the East End, as did thousands of men, including Barnett and Kosminski. His mother’s residence on Cable Street doesn’t prove he visited her during the murders – it’s speculative.

The timing of the murders doesn’t uniquely point to Cross. The double event (1:00–1:45 a.m.) and Kelly’s killing (3:00 a.m.) fall outside his typical commute (4:00–6:00 a.m.), and while he likely had Saturday night off, so did many workers, including Barnett (historical labor patterns). Cross’s lack of a flesh-cutting trade undermines the progression theory – Eddowes’ “surgical skill” and Kelly’s precision (Dr. Brown, Dr. Phillips, inquest) suggest anatomical knowledge Cross likely didn’t have as a carman, unlike Barnett, a fishmonger. Witness descriptions rarely match Cross – George Hutchinson’s “astrakhan” man (Kelly, 30-ish, well-dressed) and Israel Schwartz’s “Lipski” man (Stride, 30-ish, 5’5”) don’t fit a 39-year-old carman (inquest).

Finally, Cross lived a quiet life after 1888, raising a family and dying in 1920 without further suspicion. The police never considered him a suspect (MEPO 3/140), focusing instead on Kosminski and others with criminal or mental health records. Cross was a witness, not a killer – a man this investigation has wrongly accused.

Whitechapel Map: Marks murder sites, notes Doveton Street’s location (off the map), and highlights Sion Square (circled in blue).

The Verdict So Far

The defense makes valid points – Cross’s presence at Nichols’ scene could be coincidence, and the lack of direct evidence beyond that moment is a challenge. But his proximity, timing, and behavior keep him in the frame, outshining the others. Let’s adjust the probabilities for all suspects, factoring in the defense’s arguments, to set the stage for my rebuttal.

- Charles Cross: The defense weakens Cross’s case by highlighting the lack of direct evidence beyond Nichols and the mismatch with witness descriptions. However, his undeniable presence at Nichols’ scene, proximity to all murders, and the Mizen discrepancy still make him the strongest suspect. I adjust his likelihood to 60–65% for Nichols (down from 75–80%, factoring in the defense’s timeline argument), 50–55% for Chapman, 45–50% for the double event, and 35–40% for Kelly, with an overall probability of 40–45% for the series – he remains the top suspect.

- Joseph Barnett: Barnett’s high likelihood for Kelly (55–60%) is tempered by his lack of connection to the other victims and police clearance (MEPO 3/140). The defense doesn’t directly address him, but Cross’s case indirectly lowers Barnett’s overall fit. He stays at 55–60% for Kelly, 30–35% for Chapman, 25–30% for the double event, with an overall probability of 30–35% for the series – still in play but trailing.

- Aaron Kosminski: Kosminski’s strength in the double event (60–65%) and proximity (Sion Square) are offset by his lack of scene presence and hindsight suspect status (Swanson, 1910). The defense’s focus on Cross doesn’t change his standing – he remains at 40–45% for Kelly, 55–60% for Chapman, 60–65% for the double event, with an overall probability of 35–40% for the series – close but not enough.

- David Cohen: Cohen’s profile, echoing Kosminski’s, remains weak with no scene evidence and a late timeline (post-Kelly). He stays at 25–30% for Kelly, 30–35% for Chapman and the double event, with an overall probability of 25–30% for the series – out of the running.

Cross stands as my top suspect – Jack the Ripper, hiding in plain sight. But the defense has sown doubt, and the jury – you, the readers – must decide.

Do you agree that Charles Cross is Jack the Ripper, or did the defense sway you? Share your verdict in the comments below, and join me next time for my rebuttal – the prosecution’s final word before your judgment.