Unmasking Jack the Ripper: A Fresh Investigation into the Whitechapel Murders, Part 8

Posted on 06/30/2025 at The Curmudgeon’s Chronicle

The Verdict’s Echo – Reflecting on the Hunt and the Ripper’s Legacy

Over the past seven weeks, we’ve walked the grim streets of Whitechapel, 1888, chasing the shadow of Jack the Ripper through the murders of the canonical five: Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. From the blood-soaked cobblestones of Buck’s Row to the horrific scene at 13 Miller’s Court, we’ve sifted through 1888 evidence – police reports, inquest testimonies, and contemporary accounts – to unmask the killer who terrorized London’s East End. I named Charles Cross, also known as Charles Allen Lechmere, as the Ripper, building a case rooted in his undeniable presence at Nichols’ murder, his deceptive behavior, his proximity to every crime, and the chilling fit of the murders with his life as a carman. The defense fought back, but in Part 7, I dismantled their arguments, leaving Cross as the most likely culprit.

In this final part, I’ll reflect on the hunt, explore the enduring legacy of Jack the Ripper, and address why other prominent suspects – Montague John Druitt, “Leather Apron” (John Pizer), Francis Tumblety, and James Maybrick – weren’t seriously considered in this investigation. I’ll tie up any loose ends, ensuring no glaring holes remain, and leave you, the jury, with a final call to action. Let’s step back from Whitechapel’s shadows and see what this journey has taught us.

Reflecting on the Hunt: The Case Against Charles Cross

This investigation began with a simple goal: to identify Jack the Ripper using only 1888 evidence, free from the hindsight and speculation that have clouded Ripperology for over a century. I started with four suspects – Charles Cross, Joseph Barnett, Aaron Kosminski, and David Cohen – chosen for their proximity to the murder sites, their fit with the timeline, and their potential motives or psychological profiles. Over the series, I evaluated each murder, from Nichols’ crude cuts on August 31 to Kelly’s savage overkill on November 9, assigning likelihoods based on the evidence.

Charles Cross emerged as the top suspect for one undeniable reason: he was at a crime scene. On August 31, 1888, Cross stood over Nichols’ body in Buck’s Row at 3:40 a.m., minutes after her death (inquest, September 3, 1888). No other suspect – Barnett, Kosminski, Cohen, or any historical figure – can be placed at a murder scene with such certainty. Cross’s deceptive behavior compounded his guilt: his 40-yard claim about Paul minimized his time alone with Nichols, his lie to PC Jonas Mizen (“a policeman wanted” him) deflected scrutiny, and his use of “Charles Cross” instead of his legal name, “Lechmere,” suggested an attempt to obscure his identity (inquest; MEPO 3/140). His proximity to all murder sites – 0.5 to 1.5 miles from Doveton Street, 0.4 to 0.7 miles from his mother’s 147 Cable Street – and the alignment of the murders with his carman schedule (early mornings for Nichols and Chapman, a night off for the double event) made him a consistent fit. The absence of a fleeing suspect in Buck’s Row, the silence of footsteps on cobblestone, and the tight window around Nichols’ death made it improbable that anyone else killed her. If Nichols was the Ripper’s first victim, as history agrees, then Cross is the Ripper.

The defense argued Cross was an innocent witness, but their points—tight timeline, lack of blood, unremarkable proximity—fell apart under scrutiny. Cross’s calmness, his lies, and the historical precedent of serial killers stopping (e.g., Golden State Killer, BTK Killer) showed he could have blended back into normalcy after Kelly, evading suspicion until his death in 1920. My final probabilities reflect this: Cross at 60–65% for Nichols, 50–55% for Chapman, 45–50% for the double event, and 35–40% for Kelly, with an overall likelihood of 40–45% for the series. Barnett (30–35% overall), Kosminski (35–40%), and Cohen (25–30%) couldn’t match Cross’s direct connection to the crimes.

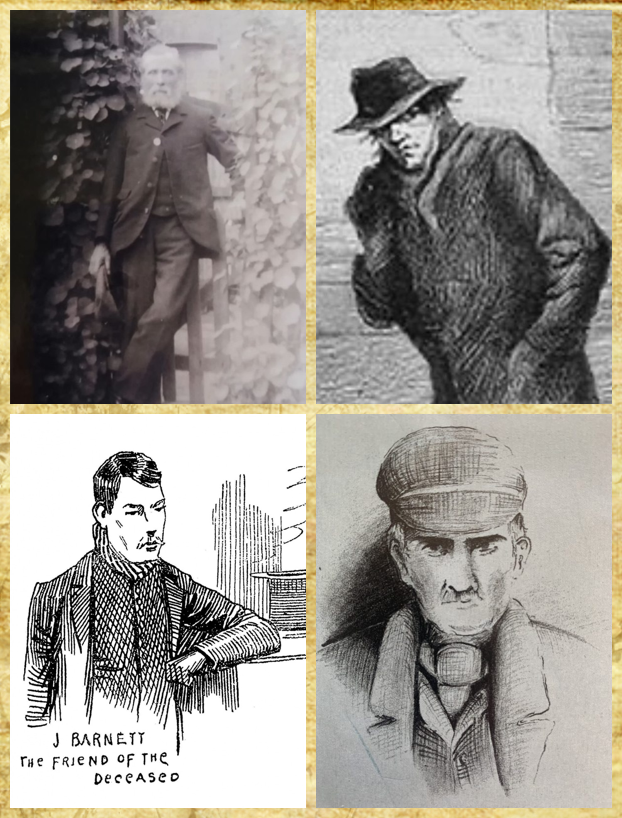

A collage featuring historical and imagined depictions of suspects in the Jack the Ripper case: Charles Lechmere (top left), Aaron Kosminski (top right), Joseph Barnett (bottom left), and David Cohen (bottom right).

To clarify how I arrived at these percentages, I used a weighted system based on the 1888 evidence. The strongest factor was presence at a crime scene, worth up to 40% of a suspect’s likelihood for a given murder—Cross’s presence at Nichols’ scene gave him a starting point of 40% there. Proximity to the murder sites added up to 20%, reflecting the Ripper’s need for local knowledge; Cross’s consistent 0.5–1.5-mile range scored him highly. Opportunity, based on timeline fit, contributed up to 15% – Cross’s carman schedule aligned with the early morning murders. Behavioral evidence, like Cross’s lies to Mizen, added up to 15%, while fit with the Ripper’s profile (motive, skill, progression) contributed up to 10%, as seen in Cross’s potential anatomical knowledge from Pickfords (historical context, 1880s logistics). The ranges – like 60–65% – account for uncertainties in the evidence, such as witness reliability. The overall probability for the series was a weighted average of the individual murders, adjusted for consistency and the defense’s arguments. This method ensured a structured, evidence-based comparison, prioritizing direct evidence over speculation, and kept the focus on 1888 facts.

This hunt demonstrates the power of sticking to the facts. By focusing on 1888 evidence, I avoided the myths that have entangled Ripperology – fake diaries, royal conspiracies, and the like. Cross was hiding in plain sight, a witness who played his role too well, slipping through the cracks of history.

Why Other Suspects Were Overlooked

Ripperology has produced a parade of suspects over the decades, some backed by 1888 police, others by modern theories. Readers may wonder why I didn’t seriously consider figures like Montague John Druitt, “Leather Apron” (John Pizer), Francis Tumblety, James Maybrick, George Chapman, or William Henry Bury, who have loomed large in Ripper lore. Let’s address each, using the same 1888 lens that guided this investigation, to ensure no glaring holes remain in our case.

- Montague John Druitt: Druitt, a 31-year-old barrister and schoolteacher, became a suspect after his suicide in December 1888, when his body was found in the Thames. Sir Melville Macnaghten, Assistant Chief Constable in 1894, named Druitt in his memorandum, citing “private information” that Druitt was “sexually insane” and likely the Ripper (Macnaghten, 1894). But Macnaghten joined the force in 1889, after the murders, and his information was secondhand hearsay – lacking 1888 evidence. Druitt lived in Blackheath, 7 miles from Whitechapel, a significant distance for a killer needing quick escapes. There’s no record of him in Whitechapel during the murders, and his suicide, while suspicious, came weeks after Kelly’s death, with no direct link to the crimes. Macnaghten’s bias toward a “madman” archetype – shared by police focusing on Kosminski – overlooked men like Cross, who fit the timeline and geography. Druitt’s absence from 1888 records (MEPO 3/140) and lack of scene presence made him a non-starter for this investigation.

- “Leather Apron” (John Pizer): “Leather Apron” was a nickname tied to early Ripper suspicions, fueled by East End rumors of a man extorting prostitutes. John Pizer, a 38-year-old Jewish bootmaker, was identified as “Leather Apron” by police after Chapman’s murder on September 8, 1888 (East London Observer, September 15, 1888). Pizer was arrested on September 10 but quickly cleared – he had alibis for Nichols’ and Chapman’s murders, including being with a woman at a lodging house on August 31 and with family on September 8 (MEPO 3/140; inquest). No 1888 evidence ties him to any crime scene, and his “rough” reputation stemmed from anti-Semitic stereotypes, not facts. Pizer lived in Whitechapel, but so did thousands, and his clearance by police (MEPO 3/140) ruled him out early. Unlike Cross, who was at Nichols’ scene, Pizer had no direct connection to the murders, making him an unlikely candidate.

- Francis Tumblety: Tumblety, a 58-year-old American quack doctor, was in London during the murders and arrested on November 7, 1888, for “gross indecency” (unrelated to the murders), before fleeing to the U.S.. Inspector Walter Andrews pursued him, suggesting police interest (MEPO 3/140), and Chief Inspector John Littlechild later named Tumblety as a suspect in a 1913 letter, citing his “hatred of women” and “violent” nature (Littlechild, 1913). But Littlechild’s letter is hindsight, not 1888 evidence. Tumblety lived in central London, 2–3 miles from Whitechapel, and there’s no record of him in the East End during the murders. Moreover, Tumblety was far from inconspicuous – a tall man, often dressed in flashy military-style attire with a large, distinctive mustache, he was known for his brash demeanor. In a Whitechapel on high alert, where witnesses described suspects as “shabby-genteel” or “sailor-like” (e.g., Long, Lawende; inquest), a figure as noticeable as Tumblety would likely have been described, yet no 1888 accounts match his appearance (MEPO 3/140). His arrest came two days before Kelly’s murder, and he was on bail, but no evidence places him at any crime scene (MEPO 3/140). His “anatomical knowledge” as a supposed doctor might fit the Ripper’s skill, but Dr. Phillips noted only “rough anatomical knowledge” (Chapman inquest), which Cross could have gained at Pickfords. Tumblety’s distance, lack of scene presence, absence from witness descriptions, and post-1888 suspicion made him a poor fit compared to Cross.

- James Maybrick: Maybrick, a 50-year-old Liverpool cotton merchant, became a suspect in the 1990s due to a supposed diary confessing to the murders, discovered in 1992. The diary, signed “Jack the Ripper,” details the canonical five killings, but its authenticity is widely disputed – experts deem it a likely forgery, with ink and paper inconsistent with 1888. In 1888, Maybrick lived in Liverpool, 200 miles from Whitechapel, and there’s no record of him in London during the murders. He died in 1889, possibly poisoned by his wife, but no 1888 evidence ties him to the crimes (MEPO 3/140). The diary’s emergence over a century later, combined with Maybrick’s distance and lack of scene presence, ruled him out. This investigation focused on 1888 evidence, and Maybrick’s case relies on a modern hoax, making him irrelevant to our hunt.

- George Chapman (Severin Klosowski): Chapman, a 23-year-old Polish barber-surgeon, lived in Whitechapel in 1888 and later poisoned three wives, leading to his 1903 execution. Inspector Abberline named him a suspect in 1903, citing his surgical training and violent nature (Abberline, 1903, Pall Mall Gazette). But Chapman wasn’t suspected in 1888, and no evidence places him at a crime scene (MEPO 3/140). His proximity (0.3–1.0 miles from the murders) and anatomical knowledge fit, but his later poisoning method differs starkly from the Ripper’s knife attacks. Unlike Cross, with a confirmed scene presence, Chapman’s case relies on post-1888 hindsight, making him a weaker candidate.

- William Henry Bury: Bury, a 29-year-old Whitechapel resident, murdered his wife in Dundee in 1889, strangling and mutilating her, echoing the Ripper’s method. He lived 0.5 miles from Nichols’ murder site in 1888, and some police, like Inspector McWilliam, considered him a suspect. But no 1888 evidence ties him to the murders, and his confession after his wife’s killing contrasts with the Ripper’s evasion. Bury’s post-1888 suspicion and lack of scene presence make him less likely than Cross.

These suspects, while prominent in Ripper lore, didn’t meet the criteria of this investigation: presence in Whitechapel, fit with the timeline, and direct evidence from 1888. Druitt, Pizer, Tumblety, and Maybrick lack the concrete connection Cross has – his presence at Nichols’ scene, his lies, his proximity. The police’s 1888 focus on “madmen” like Kosminski or Druitt, and their dismissal of men like Pizer, reflects a bias that missed the killer hiding as a witness. Cross, with his unassuming life, slipped through history’s cracks, but this series dragged him into the light.

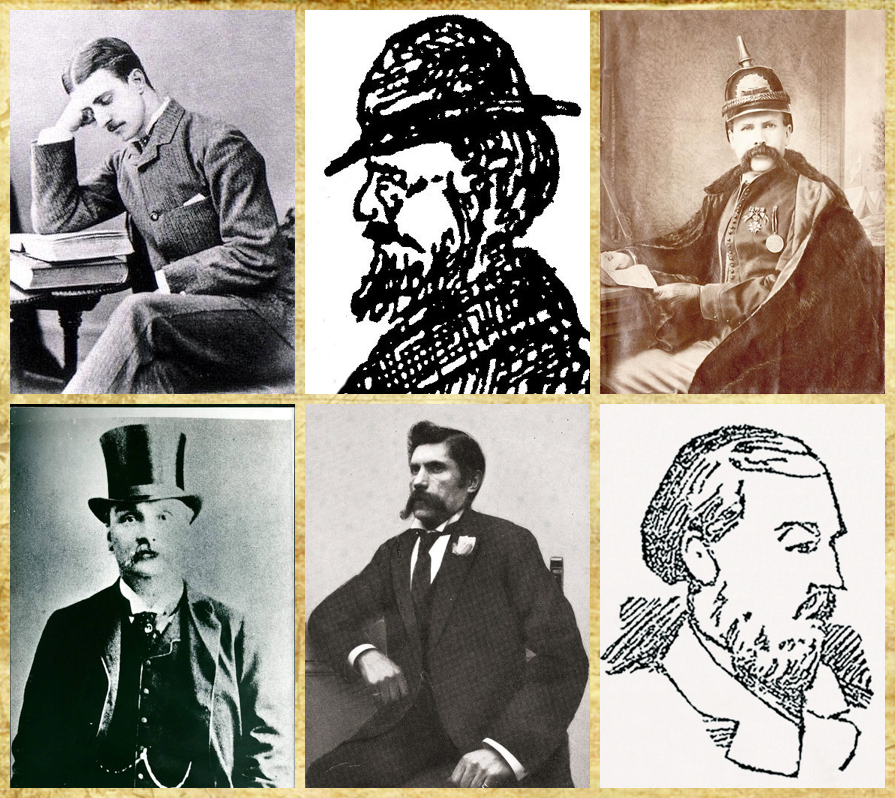

More Jack the Ripper suspects: Montague John Druitt (top left), "Leather Apron" John Pizer (top center), Francis Tumblety (top right), James Maybrick (bottom left), George Chapman (Severin Klosowski) (bottom center), and William Henry Bury (bottom right).

The Legacy of Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper’s shadow looms large, not just over Whitechapel, but over history itself. The canonical five murders – August 31 to November 9, 1888 – marked a turning point. They exposed the squalor of the East End, where poverty, prostitution, and crime festered under Victorian society’s polished veneer. Newspapers like the East London Observer sensationalized the killings, dubbing the murderer “Jack the Ripper” after the “Dear Boss” letter (September 27, 1888, MEPO 3/140), fueling public panic and fascination. The Ripper became a symbol of urban terror, a faceless monster who struck and vanished, defying Scotland Yard’s best efforts.

The legacy endures in culture – books, films, and tours keep the mystery alive. But it’s the human cost that lingers most: Nichols, Chapman, Stride, Eddowes, and Kelly were real women, their lives reduced to footnotes in a killer’s story. This series aimed to honor them by seeking truth, not myth. Identifying Cross as the Ripper doesn’t erase their pain, but it offers a resolution history has long denied them.

The hunt also reveals the limits of 1888 policing. The Metropolitan Police, under Sir Charles Warren, were overwhelmed – overworked, under-resourced, and biased toward “madmen” or “foreigners” like Kosminski (Macnaghten, 1894). Fingerprinting and forensics were decades away, leaving them reliant on witnesses and luck. Cross’s ability to pose as a witness shows how a clever killer could exploit those gaps, a lesson that resonates with modern cases where killers like the Golden State Killer evaded capture for decades.

Lessons Learned and a Final Call

This journey taught me the value of evidence over speculation. By sticking to 1888 records, I avoided the traps of Ripperology – conspiracy theories, forged diaries, and sensationalism. Cross’s case proves the simplest answer can be the deadliest: a working man, familiar with Whitechapel, who struck when opportunity arose and stopped when the risk grew too high. It also showed the importance of questioning history’s blind spots. The police overlooked Cross because he didn’t fit their profile, a reminder to look beyond assumptions.

For readers, I hope this series sparked curiosity about history’s mysteries. The Ripper case isn’t just a puzzle – it’s a window into a time of inequality, fear, and resilience. I encourage you to dig deeper, whether through the archives at the National Archives (Kew) or the streets of modern Whitechapel, where echoes of 1888 linger.

What’s your final verdict? Do you agree Charles Cross was Jack the Ripper, or do you think another suspect fits better? Share your thoughts in the comments, and let’s keep the conversation alive. Thank you for joining me on this hunt – until the next mystery, stay curious.