The Zodiac’s Shadow: Unraveling a California Nightmare

Posted on 10/20/2025 at The Curmudgeon’s Chronicle

Lake Herman Road: Blood on the Gravel

Vallejo, California, December 20, 1968. A bitter wind slices through the night, rattling the dry scrub along Lake Herman Road, a gravel-strewn ribbon where Vallejo’s teenagers chase fleeting moments of freedom. In a brown Rambler station wagon, David Faraday, 17, and Betty Lou Jensen, 16, huddle close, their breath fogging the windows. It’s their first date, a shy dance of youth – Christmas concert, diner milkshakes, and now this quiet turnout by a water pump station. The stars above promise a gentle night. But at 11:10 p.m., a .22-caliber pistol barks ten times, and blood stains the gravel. A white Chevy Impala melts into the dark, leaving two kids dead and a killer’s legend born. This is where the Zodiac’s shadow first falls – or so he’d later claim. Welcome to Part 2 of The Curmudgeon’s Chronicle’s eight-part plunge into the Zodiac Killer case, where we dissect the crime that set a California nightmare in motion. Was this his debut, or a bloody rehearsal he retrofitted into his myth? Let’s unravel the scene, the cops’ stumbles, and the ghost who started it all.

The Scene: A Lover’s Lane Turned Slaughterhouse

Lake Herman Road was no postcard. A rural stretch east of Vallejo, it was a patchwork of dirt, gravel, and lonely pump houses, flanked by rolling hills and cow pastures. By 1968, it was a known lover’s lane, where kids parked to steal kisses away from prying parents. David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen, high school sweethearts on their first outing, chose Gate 10, a turnout near a water pump station, for its seclusion. No streetlights, no houses, just the hum of a December night and the faint glow of Vallejo’s lights in the distance. Their Rambler, a hand-me-down from David’s family, was parked facing east, its nose pointed away from their Vallejo homes. Tragically, they would never make it back.

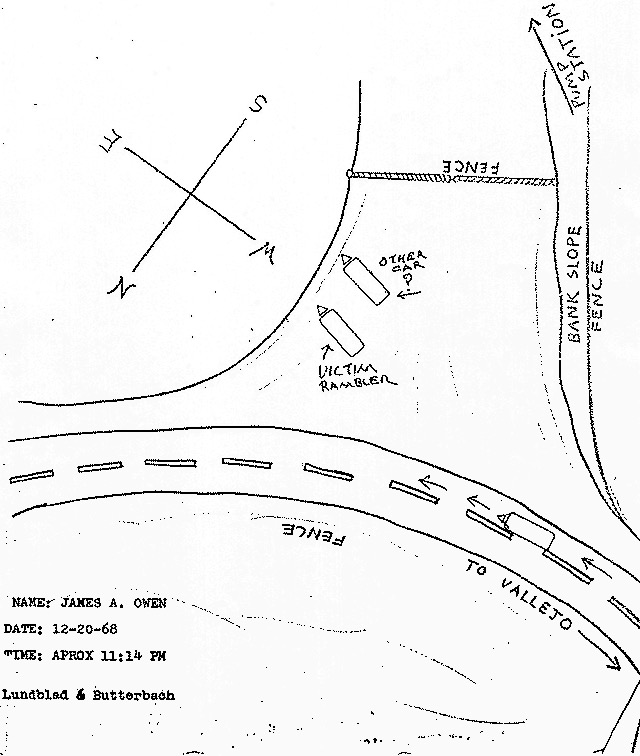

Police diagram, based on James Owen’s account, showing the Rambler facing east and another car at Gate 10, Lake Herman Road, December 20, 1968.

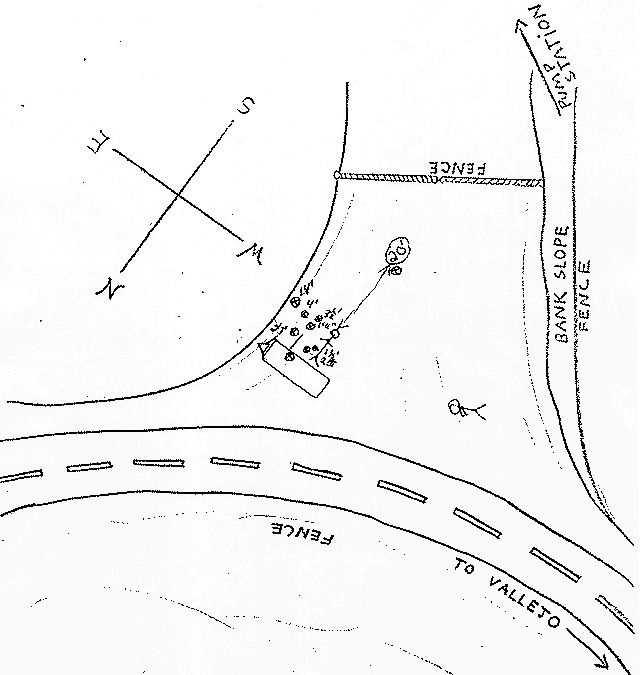

According to Vallejo Police Department reports (available via zodiackiller.com), the attack was swift and brutal. At approximately 11:10 p.m., a white Chevy Impala parked some distance – likely 20–50 feet south, per tire tracks – and its driver, the Zodiac, stalked toward the Rambler’s passenger side. Ten .22 LR Winchester Super-X rounds from a semi-automatic pistol – likely a Colt Woodsman, Ruger Standard, or High Standard Supermatic – shattered the quiet. Two wild shots punched the roof above the rear passenger window, shattering glass, and the driver’s-side floor mat, sending Faraday scrambling across the seats. Betty Lou bolted out the passenger door, running 28 feet northwest toward a fence, her shoes crunching gravel. As Faraday crawled out the passenger door, the killer advanced to the passenger-side hood, firing a .22 into his upper left ear at point-blank range, powder burns searing the skin. The bullet lodged in his jaw, no exit wound; he collapsed on his back, perpendicular to the right front wheel – feet toward the Rambler, head south – with drag marks suggesting a shuffle or involuntary spasm, perhaps from his collapse, as blood pooled under his matted hair, a lump swelling on his right cheek from the bullet’s trauma. The killer pivoted, spraying Jensen with his penlight-taped pistol, as he’d later boast. Seven shots chased her, five hitting her back in a tight 6–8-inch cluster – heart, lungs, spine, shoulder, hip – felling her face-down, her white dress stained crimson, dead by 11:15 p.m.

The crime scene was chaos preserved in police notes. Ten shots per his later boast, but cops bagged only nine casings – eight scattered south of the Rambler in a loose arc from the passenger-side hood, the farthest ~20 feet away, proving the killer stalked forward, gun blazing, with one on the passenger floorboard, likely the final spray. Six bullets hit (one Faraday, five Jensen), with four misses (two in the car’s roof and floor mat, two lost to the night) – gravel swallowed one, or he padded his tally like a carnival barker. Tire tracks, faintly visible ~50 feet east, hinted at the Impala, but no license plate or make was confirmed. Blood trails marked Jensen’s desperate sprint, pooling where she fell; Faraday’s pool spread under his head, with drag marks perhaps showing his brief movement or spasm. No fingerprints on the car or casings – gloves or meticulousness. No robbery (David’s wallet intact), no sexual assault (Betty Lou’s skirt slightly hiked, likely from the sprint and fall, but no assault signs), no cryptic notes. Just death, delivered in under a minute.

Police diagram of the Lake Herman Road crime scene, showing the Rambler’s position, nine shell casing locations, and the bodies of David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen.

Stella Borges, a local woman driving home, spotted the Rambler at 11:20 p.m. – door ajar, figures slumped – and floored it to a Creole Drive gas station to call police. Officers arrived by 11:28 p.m., their flashlights catching the glint of casings and the horror of two teenagers dead for no reason. The scene was secured, but evidence was thin. The coroner confirmed David’s single wound and Betty Lou’s five, with ballistics tying the .22 pistol to all hits, but 1960s forensics couldn’t trace it further. Cops sketched a spray of bullets, but couldn’t sketch the monster who pulled the trigger. No hairs, no fibers, no witnesses who saw the killer’s face. Just a cold trail under a colder sky.

Witnesses: Glimpses in the Dark

Witnesses were scarce, and their accounts, per Vallejo PD files, were maddeningly vague. James Owen, a local worker driving home around 11:10 p.m., passed the turnout and saw two vehicles: the Rambler and another car, possibly a white Chevy Impala, parked nearby. He didn’t stop, didn’t see a driver, and didn’t hear shots – his timing suggests he missed the attack by minutes. Owen’s statement, given days later, was consistent but useless: no license plate, no description of the car’s occupant. Was it the killer waiting, or just another couple? We’ll never know.

William Crow’s tale, though, adds a spine-chilling prelude. Around 9:30–10:00 p.m., the 19-year-old was test-driving his girlfriend’s blue sports car, pulling into the Gate 10 turnout to “check the gears.” A blue car – possibly a Valiant (Crow later said “light-colored four-door Chevy,” driven by a short-haired man with glasses) – passed them heading toward Benicia, braked hard, and reversed right back to the turnout, lights flashing ominously. Spooked, Crow floored it out of there, rocketing toward town. The mystery car gave chase, tailgating at high speed, its headlights glaring like accusatory eyes. Crow shook it by veering onto the Southampton Road exit; when the pursuer pulled over briefly, per the police report, Crow "yelled about kicking his —." The driver just sat there, then peeled away into the night. His girlfriend backed the fear factor, but not the face-to-face. Police chalked it up to road-rage flirting gone sideways – memory’s a slippery eel in the dark, especially when you’re a kid more worried about curfew than crooks. But in Zodiac hindsight? That’s no coincidence; it’s a predator scouting his stage hours early.

A third witness, a hunter named Robert Connelly, with hunting partner Frank Gasser, reported seeing a white car parked at the gate on Lake Herman Road earlier that evening, but his account was fuzzy – time unclear, driver unseen. These glimpses, logged in police reports, were the best Vallejo PD had, and they amounted to squat. A white Impala in ’68 Vallejo? That’s like chasing a ghost in a sea of tailfins – good luck, Sherlock. Without a suspect or a plate, the lead evaporated.

1968 Vallejo: A Cauldron of Quiet Tensions

To understand Lake Herman Road, you need to feel 1968 Vallejo. This wasn’t San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, with its tie-dye and sit-ins. Vallejo was a blue-collar port town, home to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, where workers punched clocks and kids dreamed of escaping to San Francisco’s glitter. The late ’60s brought tension: Vietnam War protests simmered, hippies clashed with hardhats, and lover’s lanes like Lake Herman Road were both a refuge and a risk. Teenagers flocked to these remote spots, drawn by cheap cars and cheaper thrills, but parents and cops knew they were magnets for trouble – petty crime, fights, or worse.

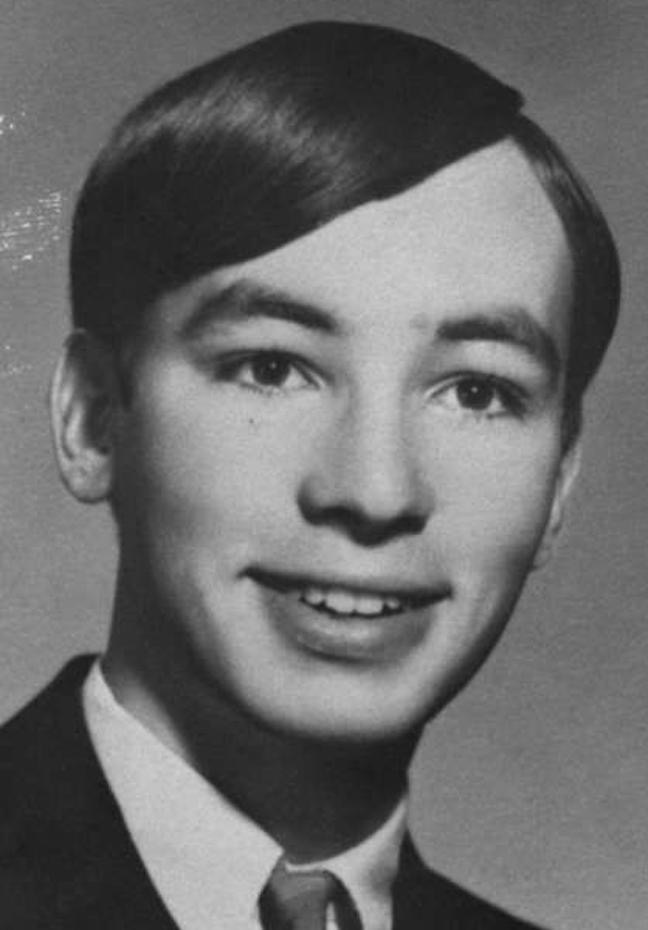

David and Betty Lou fit the Vallejo mold: good kids, high schoolers with curfews and dreams. David, a senior at Vallejo High, was an Eagle Scout, polite, with a part-time job. Betty Lou, a junior, was an honor student, shy but bright. Their first date, per friends’ statements to police, was a big deal – they told her parents a Christmas concert at Hogan High, then a stop at a mutual friend's house and Mr. Ed’s Drive-In for cokes and fries. They weren’t rebels; they were kids caught in a moment when Vallejo’s quiet facade hid darker currents. The town’s 60,000 residents felt safe, but 1968 was a year of unease: Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, RFK’s murder, and the Zodiac’s shadow looming unseen.

David Faraday, 17, an Eagle Scout and senior at Vallejo High, on his first date the night he was killed.

Betty Lou Jensen, 16, an honor student and junior at Hogan High, tragically lost on her first date.

Lover’s lanes were Vallejo’s open secret. Lake Herman Road, like Blue Rock Springs a few miles away, was a go-to spot for couples. Police patrolled sporadically, but budget cuts and small staffs meant places like Gate 10 were wide open. The Zodiac – if it was him – knew this. He picked a spot where solitude was guaranteed, where a .22’s crack would echo into nothing. Unlike Jack the Ripper’s crowded Whitechapel, where screams drew crowds, Lake Herman’s isolation was the killer’s ally. Vallejo’s innocence, its trust in quiet nights, made it the perfect stage for a predator finding his stride.

The Investigation: Vallejo PD Stumbles Out of the Gate

Let’s not sugarcoat it: Vallejo PD wasn’t ready for this one. In 1968, their small force – per FBI records – was built for bar fights and speeding tickets, not a phantom with a .22. The Lake Herman Road scene was locked down by 11:30 p.m., but the evidence work was half-baked. They bagged shell casings, sure, but didn’t bother casting tire tracks. The Rambler was towed, and dusted for prints, but nothing usable was found. The killer was either very careful, or very lucky. The coroner’s report, thorough on wounds, could only muster “close range” for the shooter’s position. Ballistics pegged the pistol and Winchester Super-X ammo – common as mud in rural California – but tracing it led nowhere; no gun shops or local hunters fit the bill.

The cops chased shadows. They leaned on David’s buddies, sniffing for a jilted rival, and grilled Betty Lou’s ex, who had a rock-solid alibi. A local hunter toting a .22 got a hard look but was cut loose – no connection. The white Chevy Impala, seen by three witnesses (including Crow’s chaser), was their best shot, but sifting through DMV records in ’68 was like panning for gold in a landfill. No car, no suspect. By January ’69, the case was iced, labeled a random killing. Police notes, now public, read like they threw up their hands: no motive, no leads, no dice.

Compare this to our Ripper series, where 1888 Scotland Yard at least had inquests and witness sketches, however flawed. Vallejo PD had 1960s tech – ballistics, blood typing, basic fingerprints – but no system to connect dots across jurisdictions. When the Zodiac claimed the murders in August 1969, the cops were caught flat-footed, their evidence too stale to test his story. Spare me the “deep state black-ops” hogwash – this was just a small-town force out of its depth, not some X-Files fever dream. The killer ran circles around them, but let’s be real: the deck was stacked. Forensics were crude, data-sharing was a pipe dream, and the Zodiac was a new kind of beast. Vallejo PD didn’t so much drop the ball as fumble a game they barely knew how to play.

The Zodiac’s Claim: Truth or Taunt?

Here’s the rub: the Zodiac didn’t claim Lake Herman Road until August 1, 1969, when he sent identical letters to the San Francisco Chronicle, Vallejo Times-Herald, and San Francisco Examiner, each with one part of the 408 cipher. Those letters listed specifics to prove his guilt: “brand name of ammo Super X,” “10 shots were fired,” “the boy was on his back with his feet to the car,” and “the girl was on her right side feet to the west.” The 408 cipher, cracked by schoolteacher Donald Harden and his wife Bettye, reveled in his love for killing and afterlife slave scheme – “I like killing people because it is so much fun” and “when I die I will be reborn in paradice [sic] and thei [sic] have killed will become my slaves” – offering no specific murder details. Was this a calculated flex, or did he rely on half-remembered details?

Unlike Blue Rock Springs, where he called Vallejo PD within an hour, Lake Herman got no immediate taunt. No phone call, no letter, no symbol on the Rambler. Why the silence? Was he testing his nerve, killing without the flair he’d later hone? The seven-month delay – until August – suggests he waited to build his myth, perhaps refining his game. The letter’s details (ammo, shots, positions) could’ve come from news leaks or gossip in tiny Vallejo, where the murders dominated headlines. Yet his August 4 follow-up, responding to Captain Bird’s plea, added the penlight trick and “high hills & trees,” details unreported then. Here, in that August 4 letter, he christened himself “Zodiac,” a name born from Lake Herman’s blood.

The Zodiac’s Mind: A Killer Finding His Voice

What drove the Zodiac to Lake Herman – if it was him? Let’s speculate, grounded in evidence. The 408 cipher, sent seven months later, paints a killer obsessed with control: “I will not give you my name because you will try to slo(w) down or stop my collecting of slaves for my afterlife.” This suggests a god complex, a man who saw murder as a game. But Lake Herman lacks the flair of his later crimes – no hood, no cipher, no phone call gloating to police. The casing arc – stretching 20 feet from the hood – proves his ‘hosing’ wasn’t just talk; he stalked forward, spraying chaos with that penlight-taped pistol, a rookie learning his craft. His August 4th letter’s ‘hosing’ brag – spraying bullets with a penlight-taped pistol – mirrors the frantic 10-shot burst: two wild misses kicked it off, one dropped Faraday, and seven turned Jensen’s flight into a bloodbath, with five hits and two more lost in the dark. This wasn’t a polished act; it was a killer learning his trigger finger, raw and reckless.

Was this his first kill? Every other murder he tied to his tally – his boast of 37 victims across 1974 letters – was pure vapor: no bodies, no scenes to match (save the shaky Cheri Jo Bates link, unlikely, and perhaps a botched attempt on Kathleen Johns, unconfirmed, both to be explored later). Lake Herman? It’s the one pre-claim crime that slots perfectly – no loose ends, just a lovers’ lane ambush in the “high hills & trees.” If it were a bluff, why pick the only real fit and risk the timeline gap? Why describe the penlight spray when papers never mentioned it? Nah, this was raw debut: a narcissist dipping his toe in blood, then watching the cops flail before stepping up to claim the script. The .22 pistol, a hunter’s sidearm, lacks the drama of the 9mm Luger he’d use next. He wasn’t just a killer; he was a chess player learning the board, and this opening gambit set the stalemate.

Suspects: Shadows Without Faces

No suspect emerged in 1968, and even now, Lake Herman offers no smoking gun. Using the weighting method from our Ripper series – presence at the crime scene (40%), proximity to Vallejo (20%), opportunity based on timeline (15%), behavioral evidence (15%), and profile fit (10%) – let’s size up the main players, sticking to 1968–1974 records and verified forensics (2002 DNA, 2020 340-cipher decryption). No anagrams or “Ted Cruz was the Zodiac” nonsense.

- Arthur Leigh Allen (1933–1992): Vallejo resident, minutes from Lake Herman Road (20% proximity). Owned a .22-caliber weapon, per 1971 police interviews, and his Zodiac watch screamed “suspicious” (10% behavior). Michael Mageau, the Blue Rock Springs survivor, ID’d him in 1991, but that’s no help for 1968 (0% presence). No alibi for December 20 (10% opportunity), and his creepy loner vibe fits the profile (5%). The 2002 DNA and fingerprint tests cleared him, gutting his case. Total: 45% for Lake Herman, 15% overall. He’s the best bet, but “best” here means “not impossible.”

- Paul Doerr (1927–2007): Vallejo local, cipher enthusiast, violent past, per Jarrett Kobek’s 2022 book (20% proximity, 10% behavior). No known .22 ownership or crime scene link (0% presence, 5% opportunity). His cipher obsession makes him a dark horse for later letters, but Lake Herman’s raw violence feels off for a meticulous planner. Total: 35% for Lake Herman, 15% overall. Intriguing, but paper-thin.

- Gary Francis Poste (d. 2018): The Case Breakers’ 2021 poster boy, with scars and anagrams the FBI laughed off. Possible Vallejo ties (10% proximity), but no 1968 evidence (0% presence, 0% behavior, 0% opportunity). Total: 10% for Lake Herman, 10% overall. Enough with the anagram obsession – it’s not evidence, it’s Scrabble.

- Richard Gaikowski (1935–2004): San Francisco journalist, not Vallejo-based (10% proximity). His voice resembled the Zodiac’s calls, per fringe claims, but no link to Lake Herman (0% presence, 5% opportunity, 0% behavior). Total: 15% for Lake Herman, 10% overall. A stretch, at best.

Allen leads, but it’s a weak lead. The white Chevy Impala could fit any of them – or none. Vallejo’s auto shops churned out Chevys like burgers at Mr. Ed’s. Without fingerprints, DNA, or a witness who saw more than a taillight, we’re chasing ghosts. The Zodiac planned it that way, leaving just enough to taunt us.

Why It Matters: The Blueprint Begins

Lake Herman Road was the Zodiac’s opening move – or so he wanted us to believe. Its isolation, quick execution, and lack of trace evidence became his blueprint for Blue Rock Springs and Berryessa. Unlike Jack the Ripper’s Nichols murder, where Whitechapel’s chaos hid Charles Cross’s tracks, Lake Herman’s solitude was the killer’s shield. The .22’s crack faded into the night, and Vallejo’s small-town cops were no match for a mind already plotting ciphers and taunts.

The police’s failure set the tone. Evidence was mishandled, leads fizzled, and jurisdiction squabbles – later worsened with SFPD and Napa County – let the Zodiac run free. Compare this to Ripper’s 1888 inquests, where at least witnesses testified. Vallejo PD had 1960s tools – ballistics, tire tracks – but no system to connect them. The Zodiac exploited that, and by the time he claimed the crime, the trail was ice-cold. Lake Herman wasn’t just a murder; it was a lesson in evasion, one he’d perfect over the next year.

Coming Up: The Voice of a Killer

Next week, we hit Blue Rock Springs, July 4, 1969, where Darlene Ferrin died and Michael Mageau survived, and we hear a monotone voice claim his sins. A 9mm Luger, a blinding flashlight, and the 408 cipher’s grand debut – it’s where the Zodiac found his swagger. Did Darlene know her killer, or is that just small-town gossip? We’ll unravel the rumors, the cipher, and why the cops were already outplayed.

What do you think? Was Lake Herman Road the Zodiac’s first kill, or a practice run he claimed to build his myth? Drop your thoughts below or on X with #ZodiacKiller.